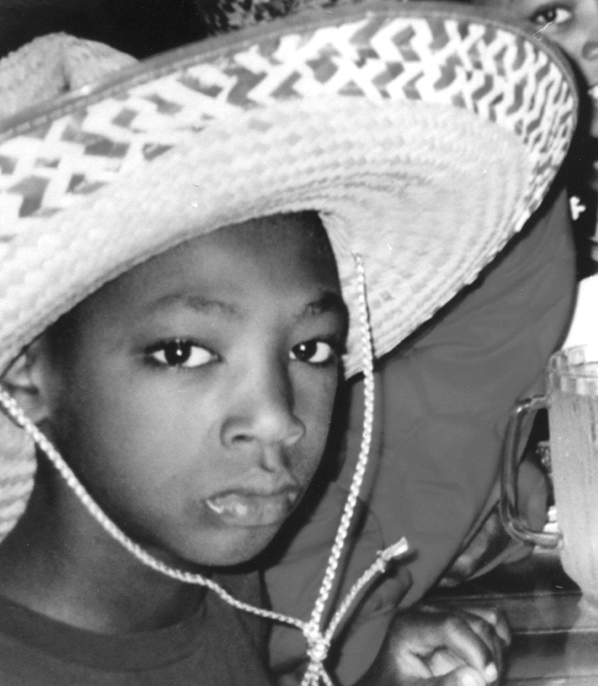

On Christmas Day 2002, Brian Boothe was found dead in his apartment in Stuyvesant Town, in Manhattan, victim of a knife wound to the neck. “Police sources” tagged it a suicide in several newspapers.

Boothe’s brother Tommy had died by suicide. New York newspapers, and perhaps the police, connected those dots: A gay male spending Christmas Eve alone, whose brother had recently taken their own life…it had to be suicide. But Brian had not spoken to his brother in years. None of the Boothe family had.

“We kept saying ‘It’s got nothing to do with it,'” says Boothe’s mother, Kay, from her home in Patchogue. “Brian was the least affected by [Tommy’s] death.

And Brian Boothe, by all accounts, was happier than ever. He would be heading to Long Island for Christmas dinner the next day, relishing in giving his 3-year-old nephew and godson Owen another toy with plenty of loose pieces, a practice that annoyed his sister-in-law. When his friends talked about foregoing their beloved annual ski trip to Aspen, he fiercely objected, charging the $4,000 for the January 19 vacation to his credit card. His friend Lisa Steinbring, who had lunch with him the day before his death, recalls how Boothe was “gleeful [while] describing the soon-to-be arrival of [his brother’s baby girl] Cassidy.” Christmas cards he wrote to his family were full of hope for the new year. To everyone who knew him, Brian Boothe was loving life.

But that didn’t stop the New York tabloids from positing suicide. And it took the medical examiner four months to officially declare Brian’s death—the result of a vicious slice to the throat—a homicide. Still, the police are sharing none of the details of the investigation with the family. “They won’t tell me much about the crime scene,” says Boothe’s sister, Donna Kukura of Shirley, “because I’m a family member, and they think it was someone he knew, he trusted.”

Friends and family will converge on St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan this Saturday, wearing “JUSTICE for Brian” pins on their lapels, for a memorial. Maybe afterward they will caravan out to the Island, to the Ground Round on Montauk Highway in Bay Shore, where Booth #287 is dedicated to Boothe, who was a server there for five years. The family will look warily at the faces in the crowd, as they did at the funeral in December, to spot any odd people or odd behavior. “You don’t know who you’re dealing with,” says Kukura. “Everyone’s a suspect.” The police put that thought in the family’s heads. Regardless, people will be there to remember a Long Island boy who moved to the city and made good, only to be struck down in the prime of life.

A BAKER AND BEEKEEPER

Kay Boothe remembers her son putting on song-and-dance shows in the backyard of their house on Valley Road in Patchogue. She remembers his beekeeping phase, along with the day the bees got loose and flew away (Brian cried). She remembers Brian and his brothers Jimmy, Tommy and Sean going down to River Avenue Park to move turtles from the perimeter of the park back into the marshes, safe from encroaching civilization. She remembers him staying home on Thanksgiving while his family went to the parade—because he wanted to stay in the kitchen and help cook, and the time he waited anxiously as the family tried his fresh-baked cookies, only to see everyone spit them out, realizing too late that he had substituted baking soda for baking powder. Those are the kinds of stories Kay Boothe remembers.

“Anyone he touched remembered him,” Kay Boothe says through tears. “It’s a shame whoever did this, to snuff out his life. Because he loved life. And he loved the city. I used to live in the city [and] I kept telling him, times are different and he would say ‘Oh ma, people are out at all hours.'”

Boothe wasn’t out at all hours on Christmas Eve. A creature of habit, Boothe was always in by 2 a.m.

On Christmas Eve, he left 1 Penn Plaza, where he worked at Seabrook Consultants as a human resources strategist, and went to the Gap to buy presents for his two nieces. “I don’t know [what they are] yet. I haven’t opened the Christmas gifts,” says Kukura.

He stopped at a Rite-Aid drug store, then the dollar store to get wrapping paper, before returning to his apartment, where he presumably wrapped the presents. He called his mother to finalize plans for Christmas dinner, and then went out for a drink.